Urban Agriculture for Pantries

How does fresh food make its way to food-insecure populations?

The home pantries of our dreams are always stocked, full of everything we need for any recipe or culinary experiment, at no cost. Unfortunately, that’s not quite how food purchasing works.

The reality is that most people have to go shopping for food. That process may not always be fun, but while many people enjoy picking up fresh produce from a local farmer’s market, others don’t have that privilege.

In fact, the U.S. Department of Agriculture found that 13.5 million households in the U.S., or 10.2% of households in the country, are “food insecure.” Locally, there are about 69,000 people affected by food insecurity, according to the United Way of the Greater Lehigh Valley.

Food insecurity is defined by the USDA as a “reduced quality, variety, or desirability of diet” or “disrupted eating patterns and reduced food intake.” That means tens of thousands of Lehigh Valley residents are either going hungry or having severely diminished options in what they can purchase and subsequently prepare and eat.

Charities and government food pantries work to help address the issue, by supplying provisions to food insecure and otherwise low-income populations. However, many food pantries struggle to include fresh, high quality produce in their offerings.

Food banks often send supplies to pantries, which then distribute the goods directly to their clients.

“A lot of the government food that we're receiving is more like shelf-stable items, although there are some fresh items as well,” said Allison Czapp, executive director of Second Harvest Food Bank, one of Northeast Pennsylvania’s regional food banks. “But we really want to emphasize the availability of the fresh produce.

"Lots of people donate food and then we do purchase some food ourselves with money that people donate to us,” Czapp said, “A lot of the purchased food is fresh perishable produce, perishable protein, dairy like milk and cheese.”

Because the majority of donated and government-purchased food is shelf-stable (like rice, canned goods, and boxed macaroni and cheese), it can be difficult to provide nutrient-rich fresh food.

One solution is urban agriculture. This can take the form of small farms in cities or even just community gardens.

“People have increasingly looked to urban agriculture in a couple of ways from food banks in the last 15 years: to get a bit more fresh produce into the streams of food that food banks and pantries and soup kitchens and others distribute and use,” said Domenic Vitiello, associate professor of city and regional planning at the University of Pennsylvania.

“But also,” Vitiello said, “some food banks have become much more active in supporting people and teaching people how to garden, and sometimes are actually community garden and urban farm support organizations in their own regions.”

Two such urban agriculture projects in the Lehigh Valley provide food directly to pantries in the area, as well as supplying Second Harvest Food Bank: Monocacy Farm Project in Bethlehem and Easton Urban Farm in Easton.

Gardeners and farmers can also donate food to pantries in a variety of ways, such as through Plant A Row Lehigh Valley or AmpleHarvest.org, as well as selling excess produce through national or state programs.

Monocacy Farm Project’s mission is three-pronged: feeding the hungry, caring for the Earth, and growing a healthy community, according to the organization’s website. The farm is led by project manager and farmer Eli Stogsdill, farmer Anton Shannon and project director Sister Bonnie Kleinschuster. The program falls under the umbrella of the School Sisters of St. Francis’ ministries, along with the St. Francis Center for Renewal at Monocacy Manor.

While the average U.S. farm in 2021 was 445 acres according to the USDA, the Monocacy Farm Project comprises just about 10. According to Stogsdill, approximately two acres are used each year for growing vegetables, and equivalent acreage from the previous year lies fallow with cover crops to replenish soil nutrients. Similarly, the farm has about two acres dedicated to community gardening, with one acre active and one acre lying fallow at a time.

However, they don’t just grow vegetables.

“We're working on expanding into tree crops and planting trees and forests in different ways,” said Stogsdill in a December interview. “We have a young apple orchard that was planted a number of years ago, and up until last week, we were planting more native nut and fruit trees, both within the deer fence, which is our main farm area, and then also as part of a riparian buffer along the creek.”

The farm supplies produce directly to more than a dozen community food pantries throughout the growing season. Some of them arrange pickups as frequently as once a week, so the farm always has visitors.

In addition to supplying produce to pantries, Stogsdill said the farm also provides affordable access to fresh food through its Pick-Your-Own program.

“During the season, we have about two days a week, generally, where people are invited to come and pick. And that is offered for a suggested donation,” Stogsdill said. “People can give as much or as little as they like. The people who can afford to give a little more help us give to people who don't pay for it.”

The community garden where people can grow food for themselves is a big draw for the project. But time can be a barrier to participating effectively, as Stogsdill explained.

“If someone wants to sign up for a plot for the season, both for their success and their enjoyment, and also for the weed pressure in management of the space, we ask that they at least plan for two to three times a week to be able to be there throughout the season, just to sort of stay on top of things and get the most benefit out of it.”

People who can’t commit to this two or three times a week can still participate, though, as Stogsdill and Shannon always need help. There are specific difficulties that come with running a small farm.

“Growing a diverse array of crops, in smaller quantities – every time, you have to switch tasks from one thing to another,” Stogsdill said. “It's like an extra sort of job or sort of kink in the labor flow of things.”

An evolving crop plan governs the system, he said, with a number of spreadsheets keeping everything organized.

“We're really trying to prioritize working with our neighbors so that we can get things to them in a way that just isn't possible through the larger food system,” said Stogsdill.

Easton Urban Farm

If Monocacy Farm Project is small, the Easton Urban Farm (EUF) is tiny, measuring at just about three quarters of an acre. It started as a community garden in the 1970s, was formalized and fenced-in in 1989, and then revamped in 2010. The diminutive farm on Easton park property now provides food for low-income populations of the Lehigh Valley.

The plot of land sits just on the southern border of the city of Easton, next to a playground and the Easton Area Neighborhood Center.

According to Mark Reid, EUF’s farmer and project manager, it is harder to farm in a smaller space than a large one without destroying the soil.

Because the space is so limited, Reid can’t let any areas lie fallow, as most farms are able to do. Instead, he works on a three-year rotation that moves through nightshades (like tomatoes, eggplants and peppers), brassicas (leafy greens like kale, cabbage and collards) and root crops (carrots, parsnips and potatoes).

“We're at our limit of where we can stretch the farm at the moment,” said Reid. “So it's really tight. We just do it by trial and error, by doing the best we can to keep it out of the rotation cycle. And if I feel like it's not gonna go to the rotation cycle, I at least try to plant something two years prior that really isn't in the same family if I can't do the full three year rotation. So it's tight, to be honest with you.”

Because EUF distributes some of its produce directly through the Easton Area Neighborhood Center’s pantry, Reid can get regular feedback from participants about what they want and need.

As a result, Reid said, they’re better able to address the cultural needs of their participants.

“A few years ago we had some people from the islands, the Caribbean, [who] were saying 'Oh can you grow callaloo?' I found that it's a type of Jamaican spinach. It's actually related to something called amaranth. So I was able to get some seeds. I planted those and some people just absolutely love that.”

They also grow a number of hot peppers, collard greens, and lemongrass as an outcome of similar conversations, which Reid says can lead to cultural exchanges among the pantry’s participants.

“There are just suggestions of ways people cook them,” said Reid. “If one person tried them, they'll tell their friend, and you'd be surprised. Like this year, we had a nice green, but it was swiss chard. It's similar to us crossing spinach and beets. And no one knew what it was. And by the end of the summer, people go, 'Do you have any swiss chard this week?'”

Mark Reid, Easton Urban Farm's project manager and farmer, holding Napa cabbage he grew and harvested. 12/9/2019

Mark Reid, Easton Urban Farm's project manager and farmer, holding Napa cabbage he grew and harvested. 12/9/2019

Compost! Photographed at Easton Urban Farm 12/21/2022.

Compost! Photographed at Easton Urban Farm 12/21/2022.

Almost bare kale and collard green stalks, photographed at Easton Urban Farm in December 2022.

Almost bare kale and collard green stalks, photographed at Easton Urban Farm in December 2022.

Napa cabbage, photographed at Easton Urban Farm in early December 2019.

Napa cabbage, photographed at Easton Urban Farm in early December 2019.

How to donate produce

Many anti-hunger advocates emphasize the profound value of fresh produce for people who are food insecure. And there are both local and national opportunities for individuals to donate.

AmpleHarvest.org

“The problem we're focused on is not food,” said Gary Oppenheimer, founder of AmpleHarvest.org. “It's misinformation and missing information that has resulted in food waste and hunger.

“This is not about the food itself. It's about solving the information problems that have historically kept locally-grown fresh food from getting to food pantries.” Oppenheimer said. “Once we solve the information problem, the food flows for the rest of people's lives.”

Oppenheimer likens his nonprofit’s operation to Uber or Lyft: Rather than providing people with food, he is connecting people with excess produce to donation sites where it will be put to the best use – like an informational middleman.

Though he emphasized that AmpleHarvest.org tells people not to donate anything they wouldn’t buy for their own family, Oppenheimer adds a caveat for those who are worried about donating.

“Gardeners who donate food are indemnified against frivolous lawsuits under a Good Samaritan Law called the Emerson Food Safety Act. If I donate food to a nonprofit and there's been no gross negligence on my part, if you get a bellyache, I'm not responsible. That's federal law in all 50 states,” Oppenheimer said.

There are 19 food pantries listed as partners on the AmpleHarvest.org site just within 10 miles of Bethlehem, and about 8,000 nationally. This network is mostly for backyard gardeners, but if you’re a farmer: do not fret, because there are local alternatives made just for you.

Monocacy Farm Project farmer and project manager Eli Stogsdill shows off red twig dogwood saplings being cultivated for a riverbed preservation effort at Monocacy Creek.

Monocacy Farm Project farmer and project manager Eli Stogsdill shows off red twig dogwood saplings being cultivated for a riverbed preservation effort at Monocacy Creek.

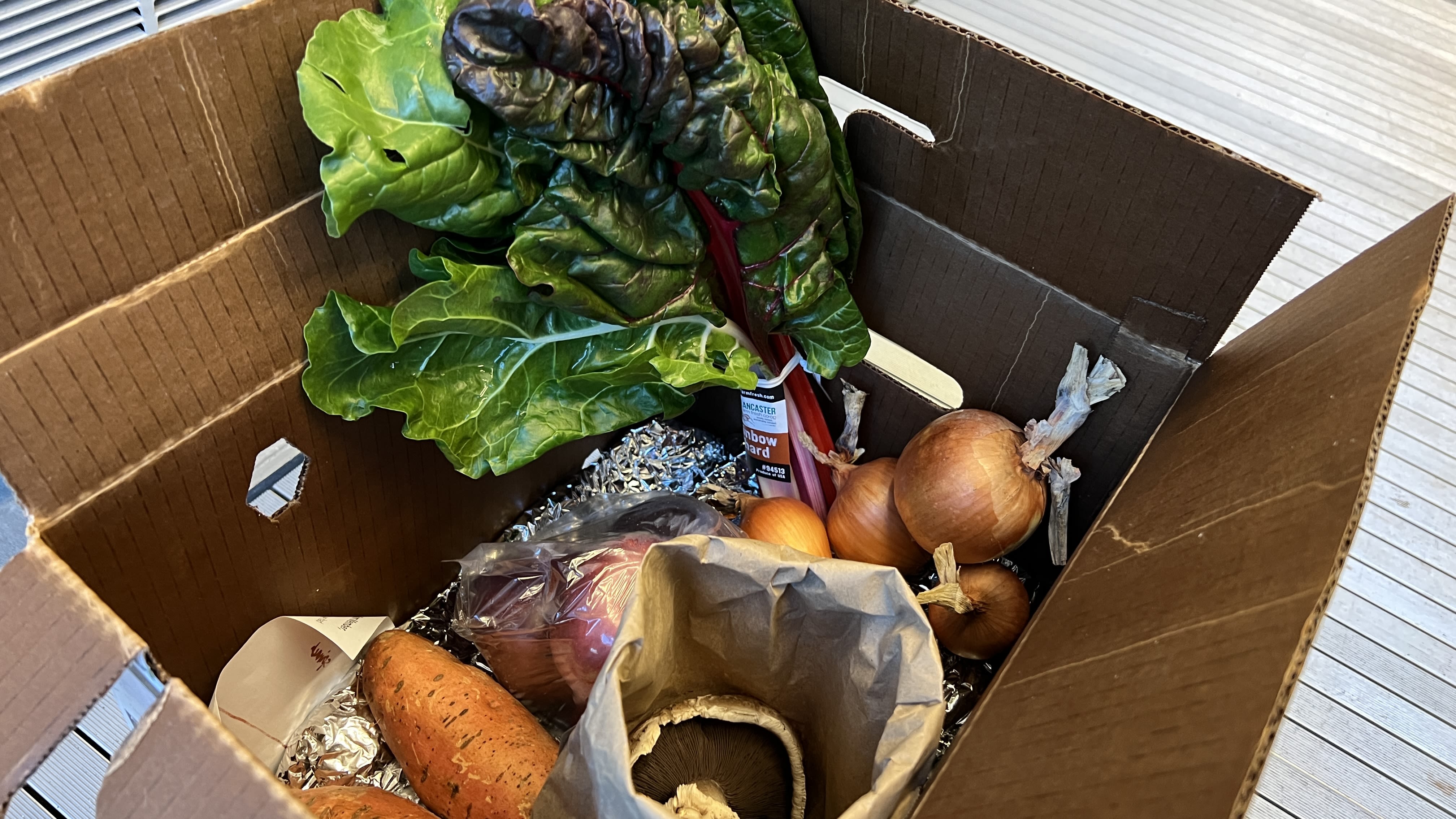

A Willow Haven Farm winter farm share box, one of the ways the farm distributes produce. Their excess is donated through Plant A Row Lehigh Valley.

A Willow Haven Farm winter farm share box, one of the ways the farm distributes produce. Their excess is donated through Plant A Row Lehigh Valley.

Plant A Row Lehigh Valley

Plant A Row Lehigh Valley is a program run by the Lehigh Valley Food Policy Council that works with both backyard gardeners and farmers. The LVFPC is a collaboration of 17 founding partner organizations designed to address food insecurity in the Lehigh Valley.

Susan Dalandan, LVFPC’s coordinator explains how “planting a row” works.

“It has its own dedicated website called PlantARowLV.org. And people can sign up on there to actually grow an extra row for a pantry or they can just sign up and donate produce. And then there are drop off points throughout the Valley.

“We have drivers drive out to the nearest pantry, we don't want to be driving things from the west side of Allentown to Easton because, you know, that's not a good use of resources. So we try to get things to the nearest pantry. And we have some farms that work with us as well, that donate their excess produce,” said Dalandan.

One farm that donates its excess is Willow Haven Farm in New Tripoli, owned and operated by Tessa and Reuben DeMaster.

“On a vegetable farm, I always have the intention of producing more food than I need,” said Reuben DeMaster. “And I do this because I don't want to run short. So when I'm successful at that, I'm always producing excess food, every single week. And there are several things that can happen with the food: It can go to animals, it can get left in the field, but I would prefer to have it donated to food pantries.”

The advantage of Plant A Row Lehigh Valley, Reuben DeMaster said, is that they coordinate the pick up and delivery of donated produce.

“It's a wonderful service for me because as a farmer, I do not have time to go to food pantries. And even though there's some food pantries that are convenient to me and not too far away, I just, I can't. I can't organize the logistics of getting off the farm and driving and dropping off at the food pantry,” said DeMaster.

Beyond Donations

Several programs have also been put into place to provide funding to get local food from local farmers.

One example is the Pennsylvania Agricultural Surplus System, which buys surplus product from local farmers and puts it into food pantries. Another is the Local Food Purchasing Agreement (LFPA), a national program aimed at supporting minority-owned farms and sending their products to food-insecure people.

“The LFPA program was directed towards Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) producers and socially disadvantaged farmers, and there are not a lot of BIPOC producers in Pennsylvania. So it's a challenge to try to find the producers that fit into that definition, by the USDA, of the socially disadvantaged farmer,” said Dalandan. “We're really trying hard to get that word out to people so that folks know that that program is available.”

Second Harvest Food Bank has partnered with local farms, including the Monocacy Farm Project, Stogsdill said.

“We started a partnership with Second Harvest, getting some small reimbursement for some of the produce we were distributing last year in a pilot program that they're excited to be expanding on.

“But we specifically grew lettuce and jalapenos for them last year, that primarily were just going to the partners that we're already working with. But we were able to get some reimbursement for our labor costs in terms of the work to distribute them, which is very helpful for us.”

Why does it matter?

When asked about why fresh produce matters, the answers advocates gave weren’t just about nutrition, some revolved around ideas of pride and shame.

Dalandan pointed out that there can be a lot of embarrassment or even fear for people using food pantries.

“There's still a lot of folks who have the feeling that, ‘I don't want my neighbor to see me in a food line.’ ‘I don't want my pastor to see me at the pantry.’ ‘I don't want my kids’ teacher to see me,’” said Dalandan.

“And if people have children, those people still very much have a fear that if they're seen in a pantry line, they're perceived as being unable to take care of the children. They're afraid of somebody reporting them to the division of human family services, you certainly do not want that. Because obviously, if you're going to a pantry, you're doing the best you can to put food on the table. It's overcoming those stigmas that are really, really important.”

Farmer Reid emphasized the importance of respecting the pride of those who patronize pantries.

“We grow lots of flowers to give to families,” said Reid. “It's nice to see people take out of the pantry a bunch of flowers, considering that they're like $15 a bunch in supermarkets. Why shouldn't people have access to flowers that brighten up their day up or to give to a relative that might not be feeling that well?”

Stogsdill echoed that sentiment.

“One big importance of it [fresh produce] is just the dignity of people, whether or not they can afford to pay for the food, getting food that tastes good, and looks beautiful, and it's going to be an important part of their diet and their culinary experience of their lives.”